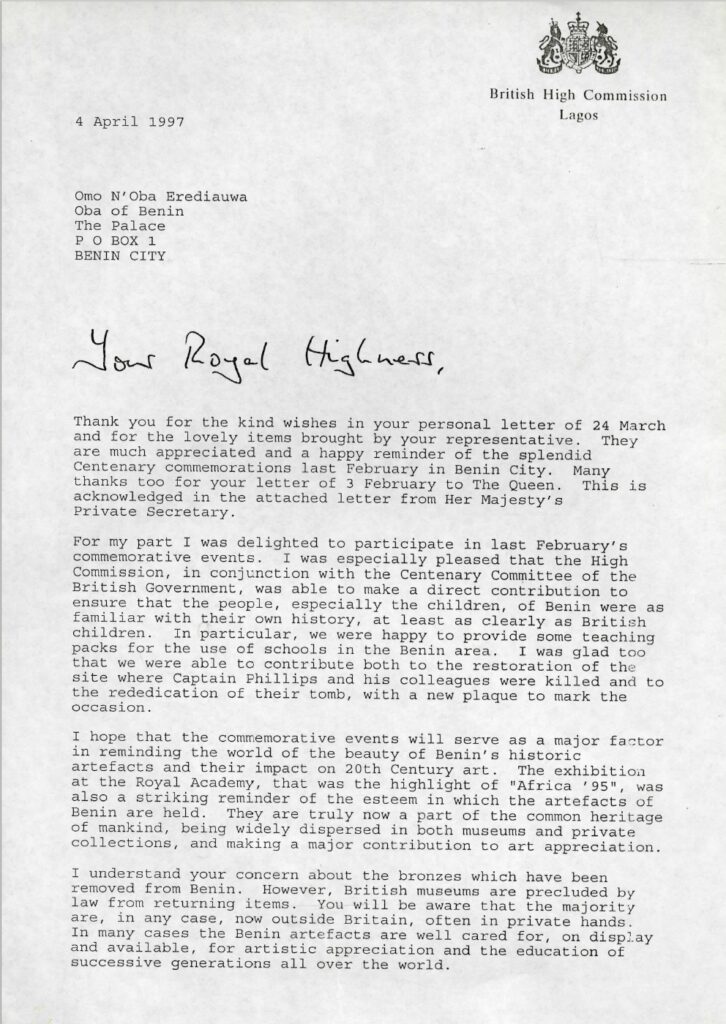

Late last year, while researching in the Bernie Grant Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute, I came across an extraordinary letter from the British High Commissioner in Nigeria to the Oba (king) of Benin. It concerned the centenary of the sacking of Benin by a British ‘Punitive Expedition’ in 1897. Benin was a centuries-old West African kingdom of the Edo people, in what is present day Nigeria. As a part of that violent episode of colonial expansion, thousands of pieces of intricate metal work, carved ivory, wood and coral, collectively referred to as the Benin Bronzes, were looted from the palace in Benin City. In the run up to the centenary the Oba had appealed to the British monarch (several important Benin pieces are in the Royal Collection) for help to return looted artefacts to Benin.

However, far from responding to the appeal for restitution, the official British contribution to the centenary was to provide some educational materials and ‘contribute both to the restoration of the site where Captain Phillips and his colleagues were killed and to the rededication of their tomb, with a new plaque to mark the occasion’.

In 1992, I was researching, with a Nigerian film director, the story of how a vast collection of Benin Bronzes came to be in the British Museum. We retraced the route taken by the party of British colonial officials and traders led by Captain James Phillips. Their ambush and killings, by Edo soldiers, provided the pretext for the full-on invasion and sacking of Benin City. The sacking of the Oba’s palace resulted in the looting of thousands of sacred and historic items, dating back many centuries, from altars and courtyards. They were taken to London and after the British Museum had acquired around a thousand items the remainder were auctioned to museums and collections across the globe. [For more on this and Bernie Grant’s 1990s campaign for restitution see here]

The river port of Ughoton was a gateway to Benin for trade with the coast and an arrival point for visitors to the kingdom, who were greeted and escorted to the city. This was where the British party landed on their misguided mission to force the Oba to accede to British ‘protection’ and one of the routes the British military invaders took a few weeks later. However, by 1992, the Nigerian road system had largely usurped the role of the rivers and creeks of the Niger delta and it was difficult to find a taxi driver in Benin City who even knew where Ughoton was. Eventually we found someone who came from the area.

In Ughoton we were greeted with a cleansing ceremony that had been described by European visitors who traded with Benin over centuries, having our feet washed in a large brass basin. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to reach Benin from the fifteenth century and we were shown fragments from a sunken Portuguese boat. But it was difficult to imagine this past activity on a quiet stretch of water with no sign of traffic and Ughoton a forgotten shadow of the town it once was.

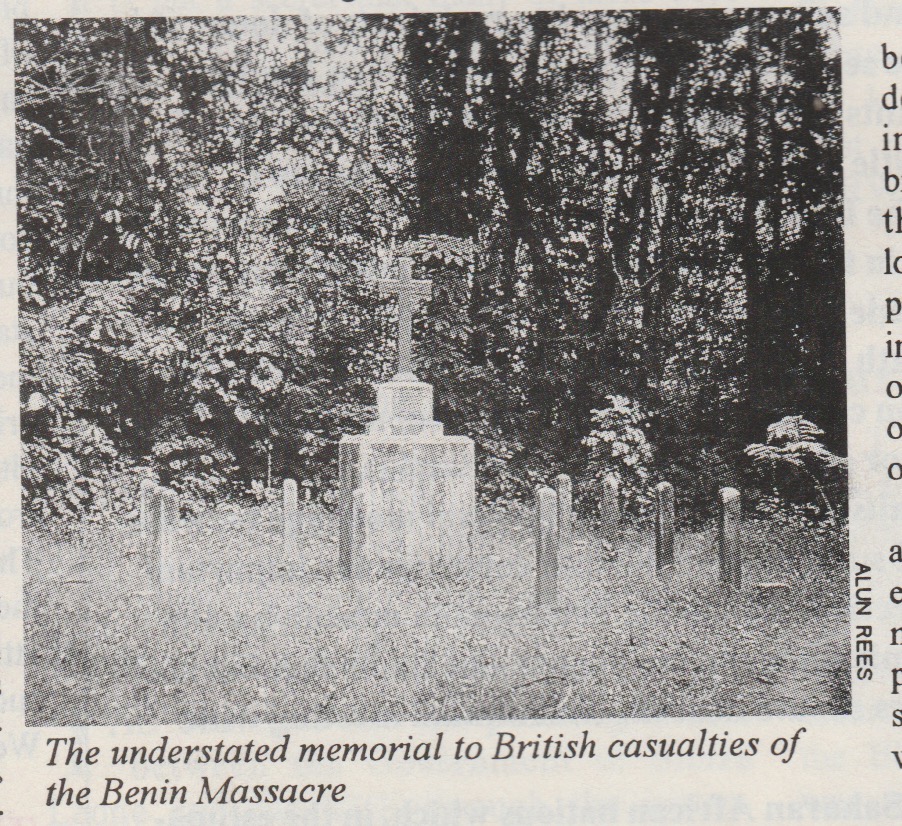

After talking to the Chief and elders of Ughoton, we set out along the path to Benin City to find the spot where the ambush had happened. It is sited on farmland outside a village called Ugbineh. After British colonial rule was imposed across Nigeria, a monument with a large iron cross was erected to commemorate the British dead – but not those from Benin or the Africans who had accompanied the party. When we arrived at the spot all that remained was a concrete base and a few of the posts that had held a chain surrounding it. Our driver, whose father’s farm was close by, did not know how or when this had happened and, maybe out of genuine respect for the dead, expressed sorrow at this ‘vandalism’.

It was only after finding the High Commissioner’s letter and connecting it with the Rhodes Must Fall campaign at Cape Town University and the subsequent dunking of Colston’s statue in Bristol in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement that I thought again about the Ugbineh monument. I wondered if it too had fallen as an act against an offensive tribute to colonialism, or if it had just become forgotten and irrelevant, the iron stripped for its value. It seems the monument has gone through many changes in the last century. The oldest photo I can find is this, held by the British Museum:

Trustees of the British Museum

I also came across a 1997 centenary copy of the now defunct West Africa magazine that featured photographs of the monument as it had been. They must have been taken some time before the 1990s, but when I tried to contact the credited photographer, Alun Rees, I found out that he had recently died and I couldn’t trace his children. Since the monument was first erected, the concrete base had been added and the wooden posts had disappeared.

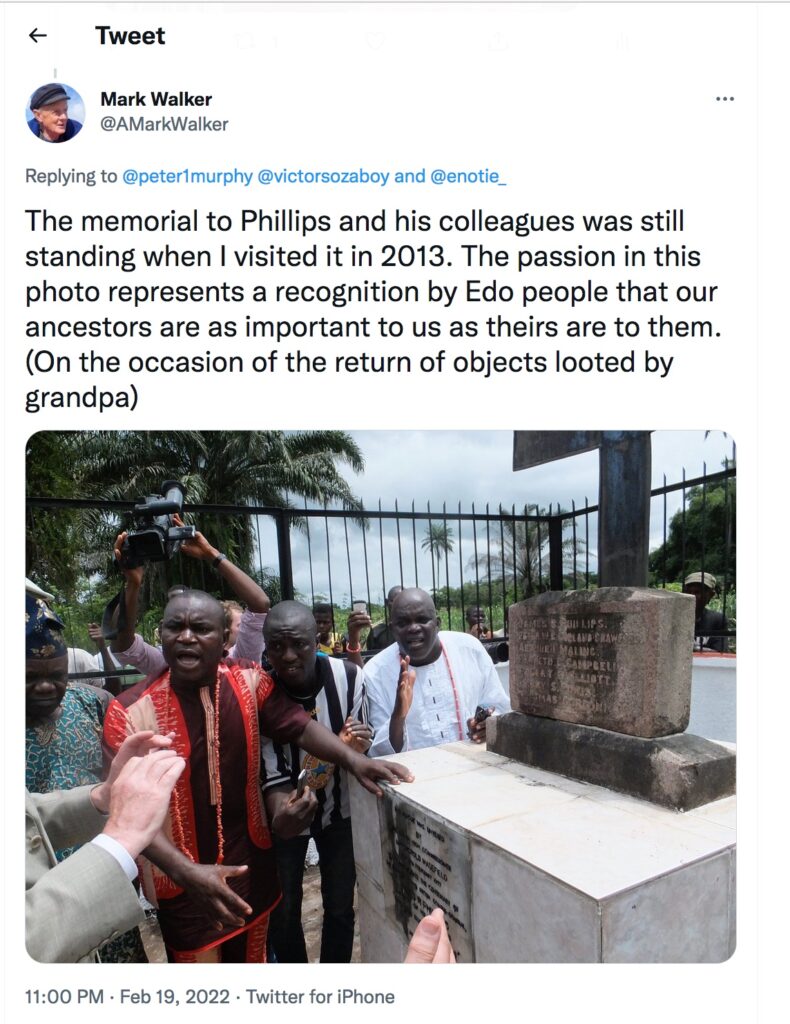

On the 125th anniversary I tweeted the High Commissioner’s letter and a query about the monument and received two interesting replies.

The first was from Mark Walker, grandson of Captain Herbert Walker, who was part of the British expedition against Benin and had kept a couple of bronze pieces and a carved ivory tusk. These were passed down from his grandmother to his parents and eventually Mark Walker came into possession of the two bronzes. Uncomfortable with keeping them as knick-knacks, he took the unprecedented step of unilaterally returning the pieces to the Oba of Benin in person in 2014. One man, on a point of principle, achieved what is still a far from completed journey for museums and institutions around the world.

Mark’s reply showed the monument as he found it on that visit less than a decade after the High Commissioner’s ‘restoration’. The inscribed stone is the same, but the cross is new and the plinth replaced or tiled over. Who had kept the inscription in the intervening years? And how did it return?

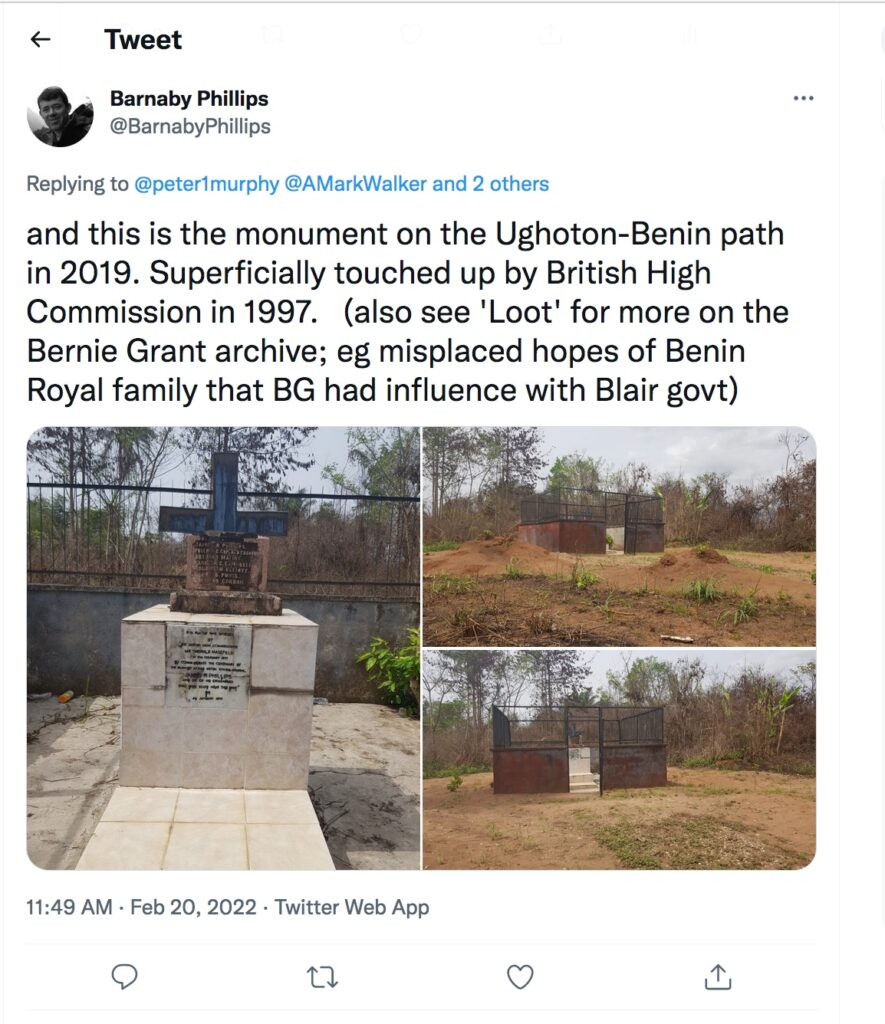

The other response came from Barnaby Phillips, whose book, ‘Loot’ tells Mark’s story in detail. He shows the monument in 2019 with a much shortened cross, within a hideous enclosure.

A provocative monument that had been almost destroyed by the early 90s has been rebuilt and undergone various changes in the last few decades. What does it mean to the village of Ugbineh, to the people of Benin? Will it continue to stand as it is? Or will there be some further response to it? Perhaps a creative rejoinder from an Edo artist, like Victor Ehikhamenor’s piece in St Paul’s Cathedral in response to a memorial panel to Harry Rawson, the admiral who led the Benin Expedition?