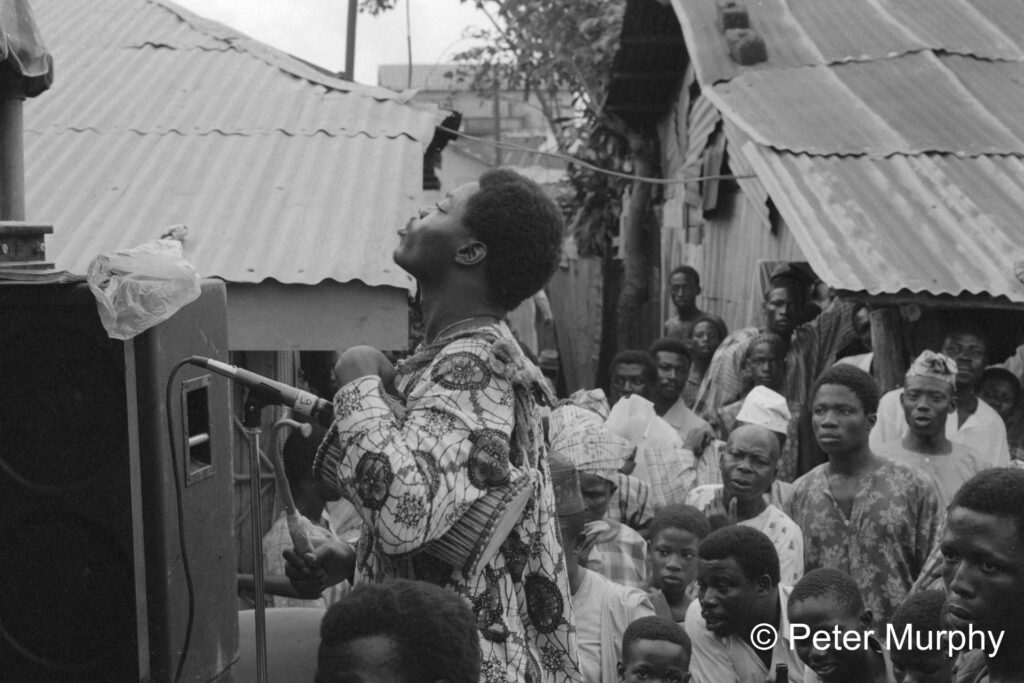

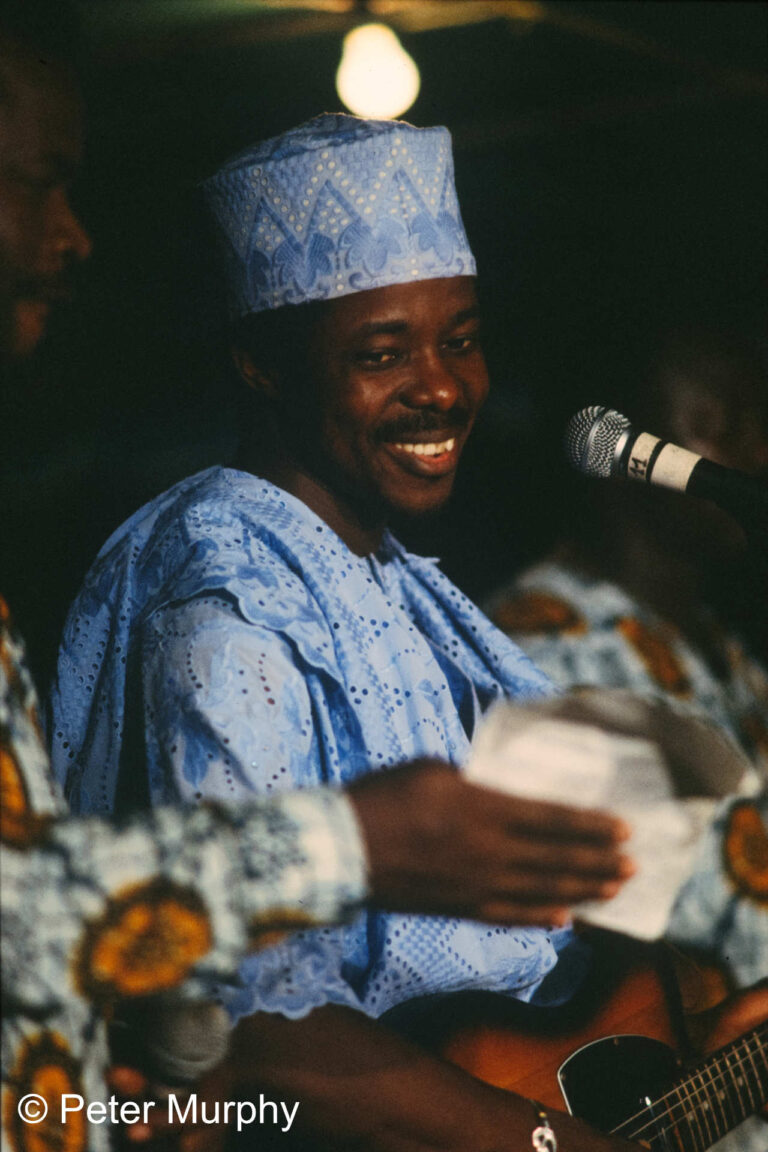

Ikorodu is around 20 miles north of Lagos, but there’s a world of difference in this short distance. On a hot, dusty Sunday afternoon it feels sleepy and provincial compared to the metropolis. Striped canopies are set up in a street of rusty zinc-roofed stores and houses for the final burial celebration of the matriarch of a large and influential family. At one end of the street a white-robed Cherubim and Seraphim church band keep up a continuous stream of hymns on guitars, drums and bugle. Small groups of talking drummers work their way through the crowd singing the praises of the dead woman, her family and guests. The mourning is over and this event is to celebrate the dead woman’s memory and send her off in good spirits. The chatter of talking drums intensifies and cuts through the din, announcing an important arrival; a buzz passes through the crowd. The drummers push their way through the throng, chanting the praises of the tall elegant figure in their midst. King Sunny Adé graciously acknowledges the praises, mounts the makeshift stage built across the street, picks up his guitar and launches his eighteen piece band into another engagement.

In 1983 King Sunny Adé and His African Beats were hot property, Nigeria’s leading jùjú band and exporters of Yoruba music to the world. They were fresh back from the most successful international tour ever undertaken by an African band but playing a burial ceremony in a dusty street instead of a prestigious concert hall.

In the early 80s Salif Keita from Mali, Youssou N’Dour and Baaba Maal from Senegal among others were selling records and touring internationally. The surprise is that it has taken so long. Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, Manu Dibango, Hugh Masakela and a few others had a dedicated following but it seemed that 1983 was the year African music really broke through. Jùjú is only one of Nigeria’s electric styles. Too culturally exclusive – the lyrics are almost always in Yoruba – it found little favour outside the west of Nigeria until bands like Sunny Adé’s, Ebeneezer Obey’s and a few others started to build a broader audience. African sounds had been making some headway in the clubs and on the airwaves in Britain for a while and Sunny Adé’s first album for Island Records, Juju Music, a collection of Nigerian hits given a major production makeover by Martin Meissonnier, was highly praised in the music press. But when he arrived in January to record his second Island album, Synchro System, promoters still thought him and his huge entourage too much of a gamble. Eventually a one-off gig was arranged, but until the night itself there was great uncertainty. Sunny himself was nervous about performing for a new audience. He was well used to performing in the UK, but almost exclusively to African student and cultural organisations in town halls, never promoted to a mainstream UK audience.

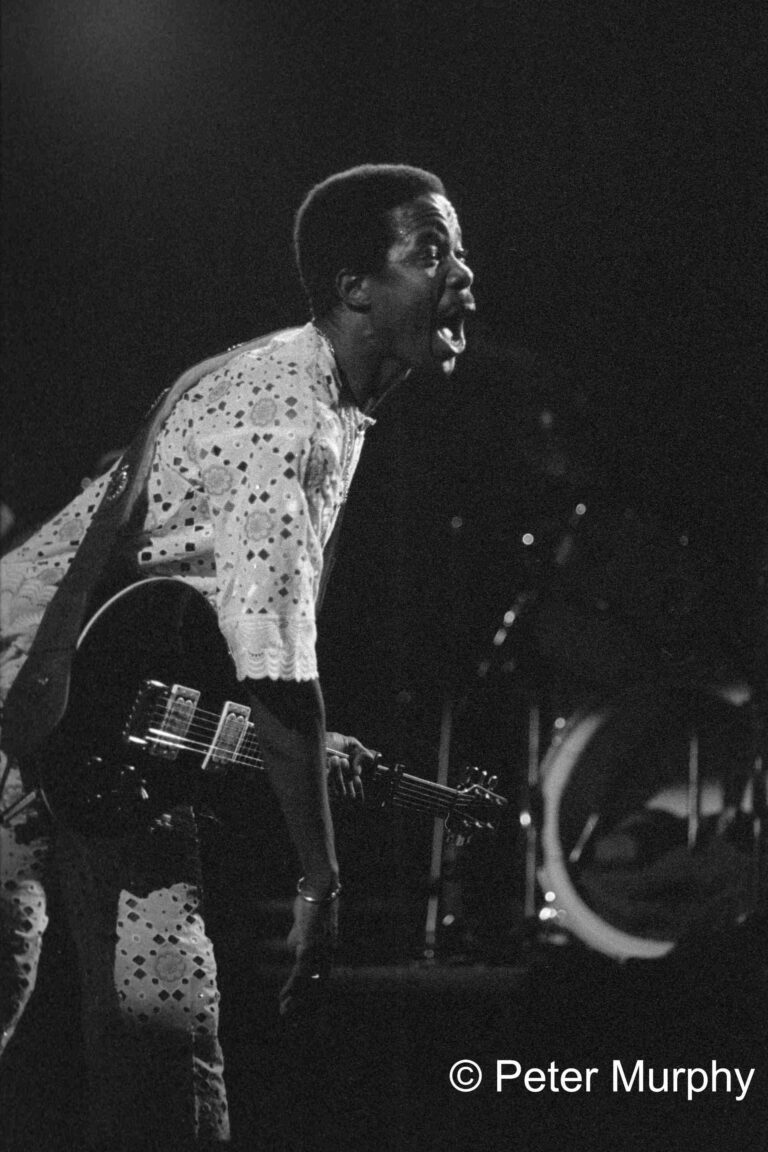

The venue was perfect, the Lyceum in London, scene of Bob Marley’s famous 1975 concert which finally broke reggae into the big time in Europe. There were inevitable overtones of that event – the buzz, the mixture of roots fans and the curious come to witness an event rumoured to be the start of something big. It seemed as though every Nigerian in London had shown up, many without tickets. For two and a half hours the Lyceum, crammed to capacity and with hundreds locked out, rocked to the rare sounds of an eighteen-piece jùjú band.

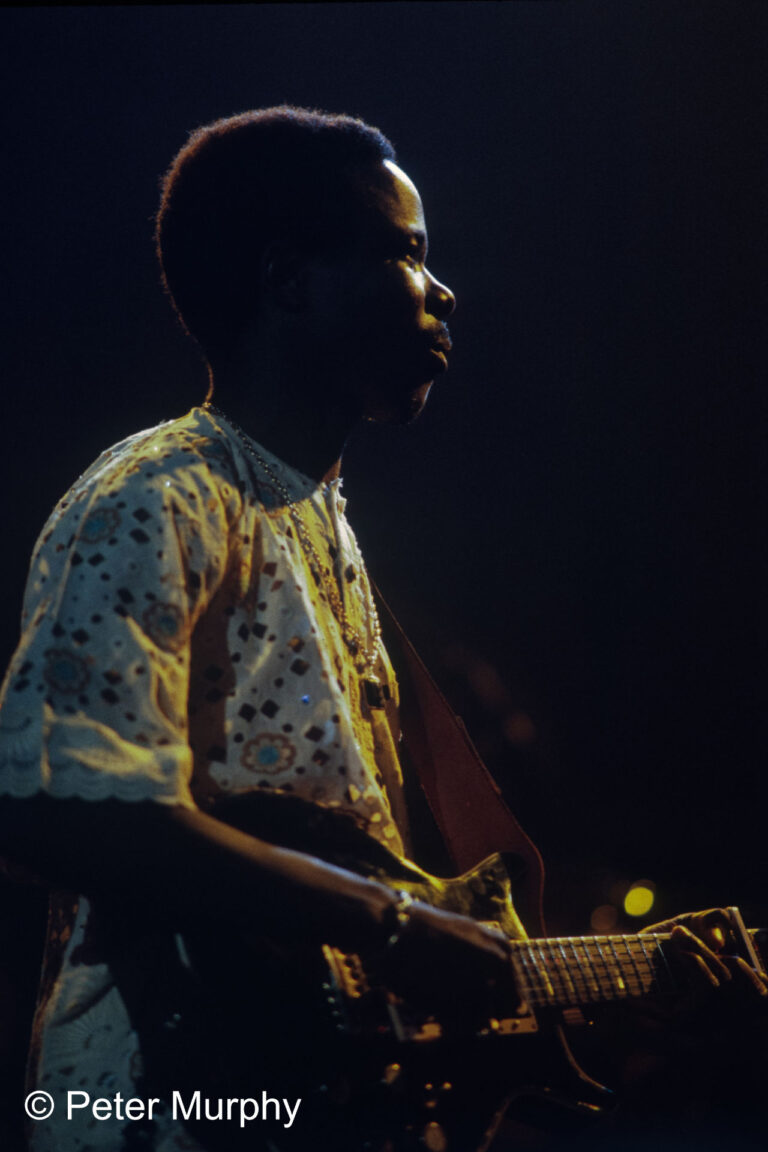

Smooth, almost crooning vocals flowed over a pumping rhythm section; jangling guitar lines interlocked and built up into crescendos. Steel guitar solos soared while bodies swirled and the talking drums added their distinctive texture, chattering away in, under and over the rhythm and concentrating into explosive runs. A sensory overload of sounds, swirling African print materials and sweat; all on a cold winter’s night. One music reviewer called it ‘the gig of the year’ – 1983 was only three weeks old. After that, tour dates were plentiful.

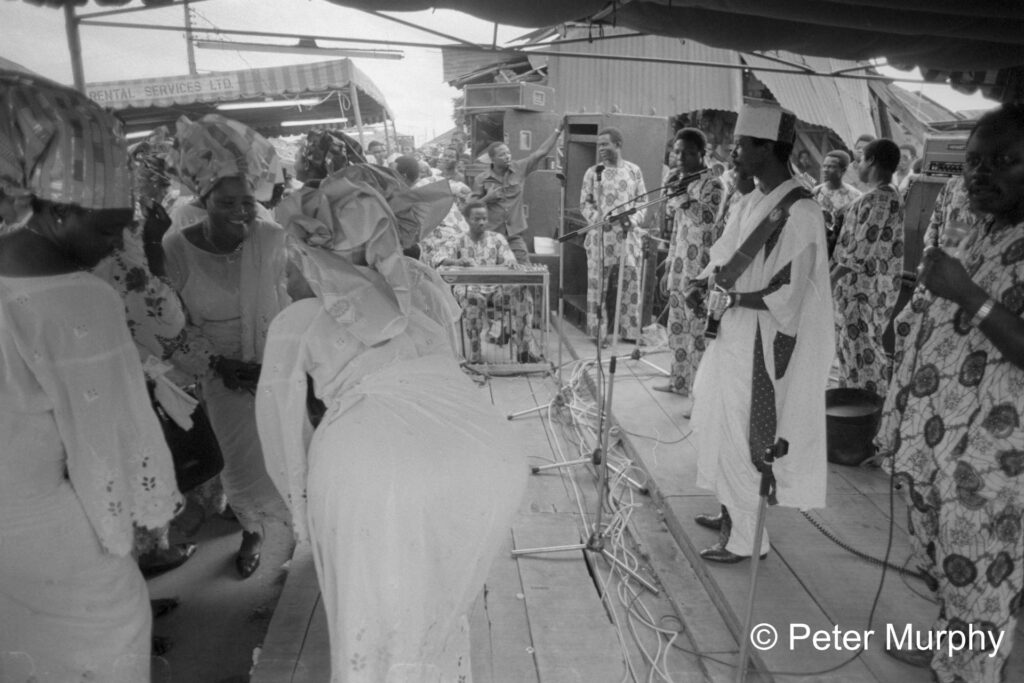

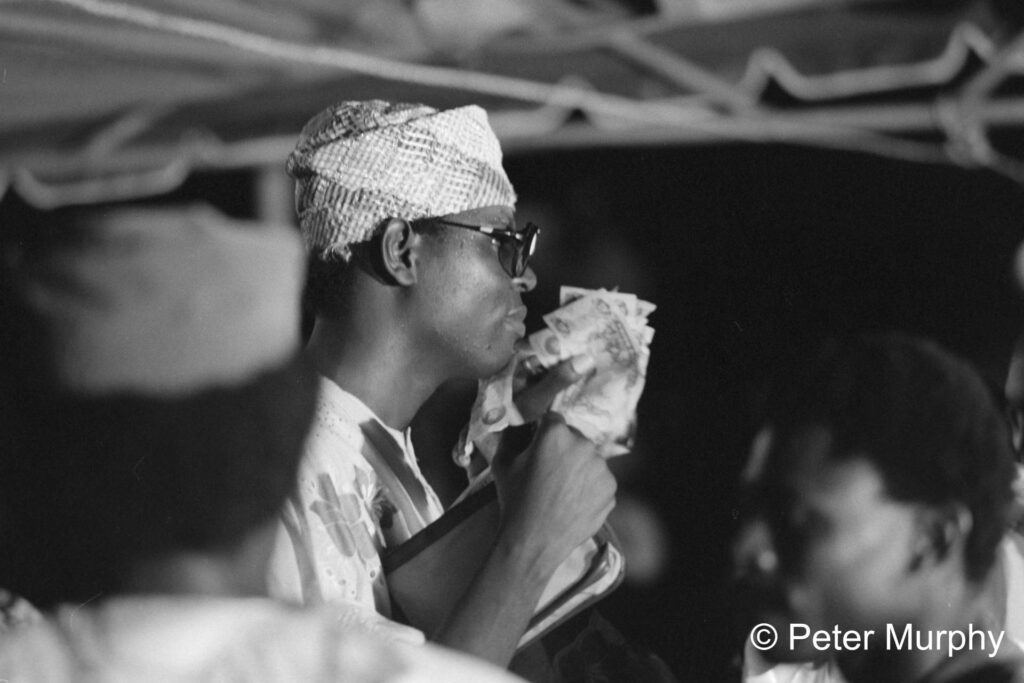

As the sun sets in Ikorodu the music flows on with barely a break. Different family groups, each dressed in matching materials specially sewn for the event, come forward and dance in front of the stage. They then mount it and ‘spray’: placing money on Adé’s head as he sings their praises. At times the stage is besieged with dancers, pushing the band back. At one point part of the stage, built over a storm drain, collapses but no harm is done and the band continue while it’s fixed.

This is very different from anything you would see the band do on a European concert stage. The steel guitar solos are stripped out and distinct songs dropped for a long litany of praises to the family and their esteemed guests. What remains is the churning percussion, pulsing rhythm and great talking drum breaks as they take up the praises and add their own comments. But when at the end, after around five hours (having played an all-nighter in Ibadan the previous night and another in Lagos the night before that), they pull out one of their real numbers you realise what was missing. These ‘private engagements’ are the bread and butter of many bands, as they have been for African musicians immemorial.

As we leave the narrow street to walk back to the band’s vehicles, Sunny is mobbed. There’s a great heaving crowd around us and he tells me to keep close by his side. He walks slowly and serenely as bedlam breaks out around us, stopping to greet an old relative of the dead woman and gently admonishing a teenager who roughly shoves a younger child out of the way. I’m being jostled but no one places a finger on Sunny Adé. At the vehicle he politely makes sure everyone is inside before calming down the noisy warring factions who each claim to have provided ‘protection’. For security reasons he doesn’t use an expensive car but a modest air-conditioned Mitsubishi minibus. At one of the many police roadblocks heading back into Lagos the police spot me in the vehicle and start questioning the driver: “where are you from, where are you going, who is this foreigner?” Sunny, in the back seat, leans forward and slides open a window, politely telling the cop that I’m a friend of his. Recognition. A great smile appears on the cop’s face and a big cheer from his colleagues as we are waved through.

Lagos, then capital of the Nigeria, was the centre of the music scene, and it was possible to experience within a week such a diversity of music that it seemed astonishing that it had not made more impact outside Africa. But Lagos was ill at ease; an urban dystopia:

‘Dem go reach house water no dey

Dem go reach bed power no dey

Dem go reach road go-slow go come

Dem go reach road police go slap

Dem go reach road army go whip

Dem go look pocket money no dey

Everday na the sametin’

– a description of Lagos life provided by Nigeria’s best known musician, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. (‘Suffering and Smiling’ Phonogram 1978)

Come darkness the choking congestion eased, the air cooled and the clubs opened. On a Friday night sounds rooted in a dozen different ethnic origins escaped from the open-air club walls and street parties. The clubs opened early in the evenings for those who couldn’t face the long journey to the suburbs, but the action didn’t start until later.

Jagged fragments of sound came from all directions, mixes of jùjú, reggae, highlife, funk from a multitude of radios, tapes and record stores, cutting through the city row alongside the amplified calls to prayer from the mosques. But also with the night, the great fear of the metropolis, armed robbers. From midnight on, taxis are hard to come by, and travelling around the city strongly discouraged. There was no official curfew but frequent harassment by armed police at the many road-blocks, meant to deter the robbers. Everyone had horror stories about murders and thefts of cars caught out during the night. Nigerian gigs have always been notoriously long, often five or six hours and the night time paranoia confirmed this pattern. Bands didn’t start until late, but then played until near dawn, when the audience feel safe to leave.

One Friday night I caught up with Sunny at his own Ariya nightclub and he told me that he was playing for a party the following night and I should come along.

Mushin is a notorious area of Lagos, a poor outsider’s quarter occupied by representatives of all the numerous ethnic groups of Nigeria, and many from beyond. However, someone from the neighbourhood who had made it big had built a fine new house here and called Sunny Adé to play for the house warming party. His guests have difficulty squeezing their Mercedes along the narrow pot-holed roads of the area.

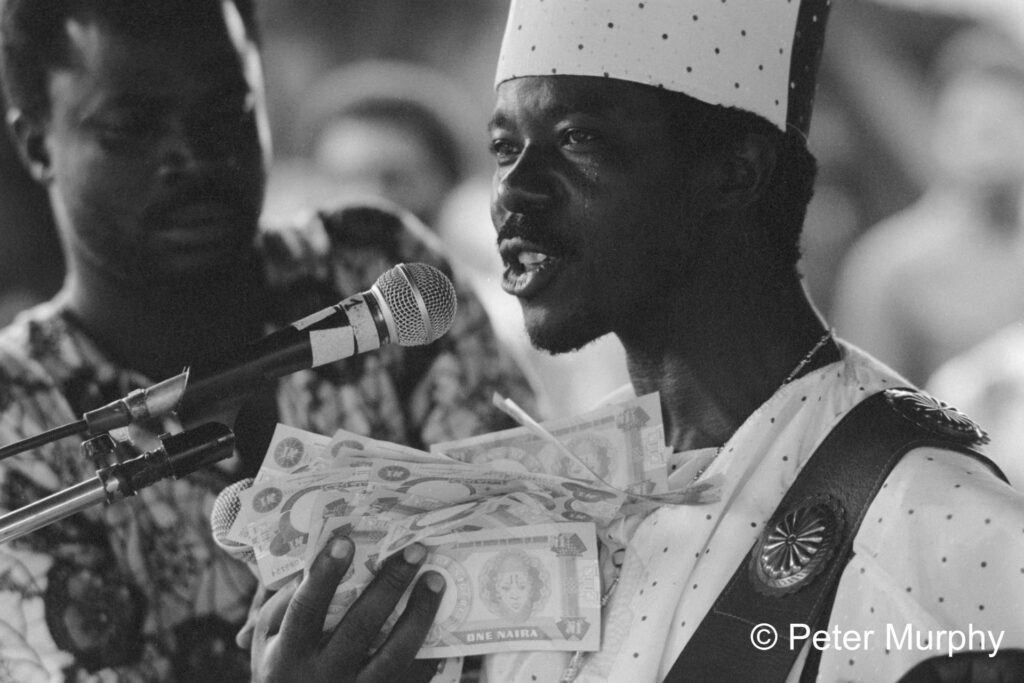

The host was determined to make this a party to remember. He climbed on stage and stayed there for half an hour ‘spraying’ money and dancing, and then returned an hour later, pockets replenished with fresh Naira notes. Follwing him a guest got up on stage with a brown paper parcel, unwrapped to reveal two brand new shrink wrapped blocks of notes fresh from the mint. He sprayed the band and finally threw handfuls of the money for the band and the youths hanging around the stage to scramble for.

This spraying went far beyond a token of appreciation. For the bands it was as much a source of income as the fee – indeed sometimes the band played for no fee at all, knowing that the host and his guests would more than make up for it on stage. It was the job of one of the band’s crew to find out who the important guests are and pass a list up onto stage. It would be humiliating to ignore your praises and the band leader would be likely to lodge a complaint with the host afterwards. Getting invited to a party could work out expensive! The host didn’t want the party to end and so at about 4.30, when it sounded as though the band, on the third all-night engagement of the weekend, were winding down, he came back and slowly doled out notes, one at a time, taking breaks to dance, dragging the show out for another hour.

I had to leave before first light as I was working out of Lagos the following day and Sunny kindly put a vehicle at my disposal to get back to the hotel. But at every turn we were confronted by barriers and watchmen armed with sticks. In frustration at the lack of security against robbers neighbours have joined together to erect barriers across their streets after midnight. In some areas vigilante groups patrol. Trying to find our way out of the maze of streets we were chased and surrounded by an armed group wearing red capes and tin helmets. The leader, brandishing a bow and arrow, his face painted white, demanded to know our business in the area. Having convinced him that we were no threat, he begged us to return to where we had come from, lock our doors and windows and sleep in the car until light, or our safety couldn’t be assured.

Sunny Adé’s international stardom peaked quickly. The first album released on Island Records, ‘Juju Music’ caused a stir, and the second release, ‘Synchro System’ sold well.But when the third, ‘Aura’, did not (despite a Stevie Wonder collaboration) his Island contract wasn’t renewed. He was clearly not going to be the ‘next Bob Marley’ – jùjú is not rebel music. Fela’s afrobeat is, but his message was primarily for a Nigerian and then African audience; Marley’s was global. The band still toured internationally and remained a festival favourite but other African artists, especially those from francophone Africa, Salif Keita and Youssou N’dour in particular, shone more brightly.

I felt there was something missing in the way that Sunny’s music was presented. There wasn’t enough of the dust, grit and atmosphere of Ikorodu or Lagos, more present in live performance than on record. Reggae seemed to tell us something about Jamaica, while jùjú, good-time party music, didn’t feel so rooted. Meissonnier’s production hinted at dub but given the reggae pedigree of Island Records maybe there could have been something more? A few years earlier, in 1979, I had played a cassette of one of Sunny’s Nigerian releases in the control room of Bob Marley’s newly built Tuff Gong studio in Kingston. Members of the Wailers were intrigued and wanted to hear more jùjú and Nigerian music. Perhaps there could have been an interesting cross-fertilisation.

However, for Sunny, the international years of touring, interviews, appearing in Hollywood films, were really a sideshow to his life in Nigeria. Releasing several albums a year, each selling 200,000+, running a nightclub and a heavy schedule of private engagements was, and remained, the core of his business. At 75 he is going strong, revered as a pioneer of a golden age of Nigerian music, still playing for parties and special events.